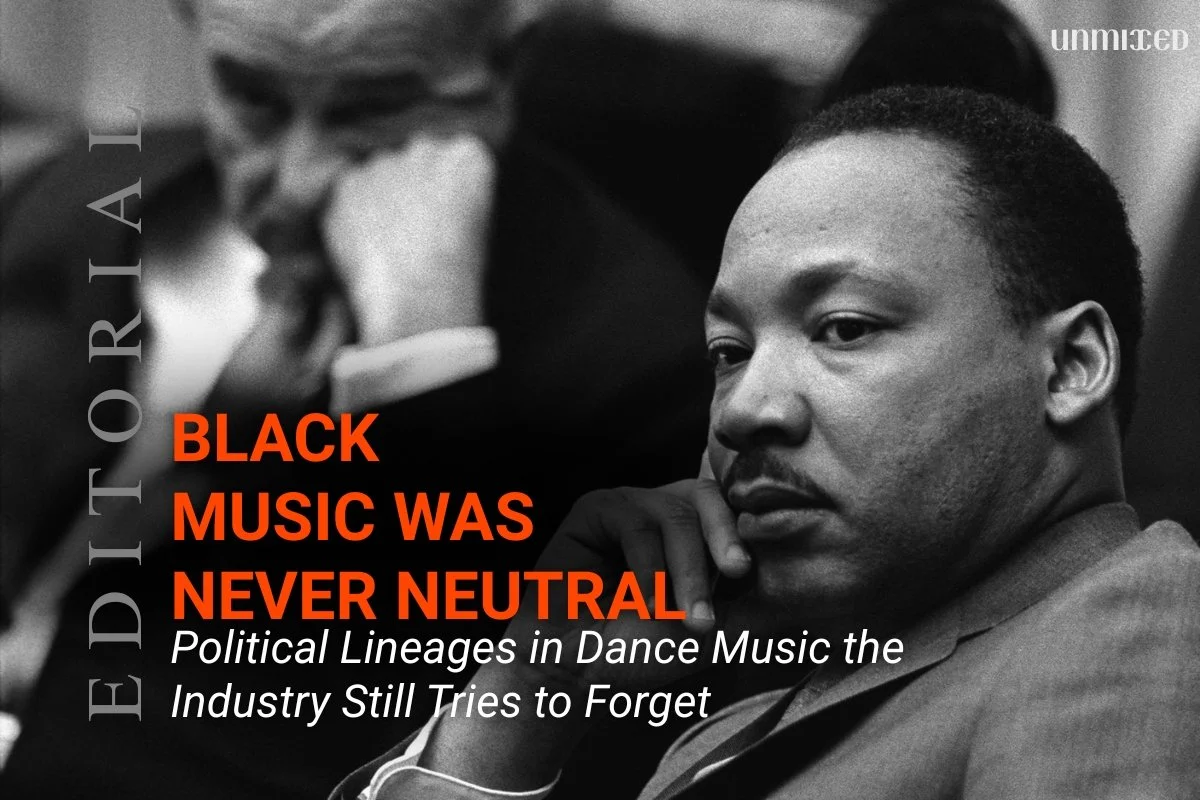

Black Music Was Never Neutral

Political Lineages in Dance Music the Industry Still Tries to Forget

A look at how Black artists built dance music as political infrastructure — and what it means to listen to that history on Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

words by Maya Lee Keezikeli

Every January, Martin Luther King Jr.’s words reappear — quoted, sampled, softened. They float through timelines and playlists as proof of “progress,” detached from the economic and racial violence he spent his final years naming directly. In music culture, this flattening is especially visible. Radical Black thought becomes atmosphere. Protest becomes mood. History becomes heritage branding.

Dance music is not immune. In fact, it may be one of the most aggressively sanitized spaces of all.

This is not a piece about influence. It’s about politics — not as slogans or statements, but as structure, refusal, and survival. Dance music did not emerge as escapism. It emerged as infrastructure: a way to build futures where none were offered, to hold space where safety did not exist, to imagine worlds beyond racial capitalism.

What follows is not a playlist. It’s a correction.

Detroit: Technology as Black Survival

Before techno was global, before it was aestheticized as “futurism,” it was a response to abandonment.

Detroit in the late 1970s and early 1980s was a city hollowed out by deindustrialization and racialized disinvestment. For Black youth, the future promised by American progress narratives simply did not exist. Techno emerged not as optimism, but as counter-planning.

Juan Atkins articulated a sonic language for futures denied. Influenced by European electronic music but grounded in Black American reality, his work reframed machines not as tools of exploitation but as instruments of self-determination.

Jeff Mills took that vision further. His refusal of celebrity, emphasis on discipline, and near-anonymous presentation weren’t stylistic quirks — they were political choices. Mills’ techno rejects spectacle and consumption. It asks for focus, presence, and submission to process.

And then there was Underground Resistance.

UR — with Jeff Mills, “Mad” Mike Banks, and Robert Hood — made politics explicit. Anti-capitalist. Anti-racist. Anti-corporate. They refused press photos, rejected industry access, and treated music as a weapon against cultural extraction. Their message was clear: techno is Black resistance music, and it does not belong to the market.

This wasn’t branding. It was operational politics.

Minimalism and Ethics

Robert Hood stripped techno down to its skeleton. Minimalism here wasn’t aesthetic restraint — it was ethical clarity. In a culture increasingly driven by excess, spectacle, and endless production, Hood’s work insists on intention.

It is very political.

And not everything needs to be loud to be radical.

Afrofuturism as Counter-History

If Detroit techno imagined futures, Drexciya rewrote the past.

Their mythology — an underwater Black civilization descended from enslaved Africans thrown overboard during the Middle Passage — was not fantasy for fantasy’s sake. It was historical intervention. A refusal to let Black history be defined solely by trauma without futurity.

Drexciya offered no faces, no interviews, no explanations. Their anonymity protected the work from commodification and demanded listeners engage with the ideas, not the personalities.

This was political theory disguised as electro.

The Club as Black Queer Infrastructure

Long before dance floors were treated as lifestyle accessories, clubs were survival spaces.

Frankie Knuckles didn’t just create house music — he helped create sanctuary. In a period defined by homophobia, police violence, and the AIDS crisis, Black queer communities built spaces where joy was an act of resistance.

Larry Levan transformed the Paradise Garage into a site of collective care. Emotional excess wasn’t indulgence — it was release. Healing. Communion.

Politics here lived in the body.

Who was safe. Who was seen. Who was allowed to feel.

Contemporary Resistance: Challenging Comfort

Political Black dance music did not end with the canon.

DJ Rashad and the Chicago footwork scene centered Black working-class dancers, not industry tastemakers. The music served its community first — speed, intensity, and repetition designed for bodies, not charts.

Hieroglyphic Being (Jamal Moss) refuses polish and algorithmic clarity. His work resists the clean narratives often imposed on Black music, embracing chaos, noise, and spiritual intensity as forms of liberation.

Moor Mother operates at the edges of dance music — and deliberately so. Her work confronts colonial violence, abolition, and Black rage without offering comfort. If dance music culture feels unsettled by her presence, that discomfort is the point.

And DeForrest Brown Jr. has done more than perhaps anyone in recent years to articulate techno as a Black radical tradition. His work refuses nostalgia, calls out erasure directly, and insists on political accountability from an industry eager to profit without remembering.

Black Women Carrying Techno Forward

That lineage did not end with its architects. It continues today through Black women and queer artists whose work resists neutrality and insists on presence.

In New York, Juliana Huxtable moves fluidly between sound, performance, poetry, and theory, collapsing the boundary between club music and political thought. Her work refuses separation between body and idea, foregrounding Black trans life not as representation but as structure.

Honey Bun approaches techno and club culture as cultural memory. Through DJing, radio, and community-centered work, she situates Black electronic music within a longer diasporic lineage, insisting that history is not an aesthetic reference but an obligation.

Operating at the intersections of techno, ballroom, hip-hop, and DIY culture, BODEGAPARTY resists genre containment altogether. Her practice reflects a politics rooted in hybridity and survival, rejecting respectability in favor of lived experience.

Artists like Dada Cozmic, Bronx-born and uncompromising, refuse the demand that Black women in electronic music be clean, coherent, or easily consumed. Her sound is confrontational and deliberately unpolished, a reminder that clarity has never been a prerequisite for truth.

Venues such as Basement in Queens have increasingly functioned as spaces where these artists are not treated as exceptions, but as central figures in the city’s underground techno ecosystem. The politics here are spatial: who is booked, who is centered, and who is allowed to experiment without apology.

In this sense, their work echoes King’s insistence that justice is not symbolic but material — something built, held, and practiced in real space.

What MLK Day Demands From Music Culture

Martin Luther King Jr. did not ask to be remembered. He asked to be heard.

He was assassinated while organizing against economic exploitation and imperial war — positions rarely quoted on his holiday. In dance music, we perform a similar ritual: celebrating Black sound while avoiding Black politics.

Sampling radical speech without engaging its meaning is not homage. It is neutralization.

Dance music was never neutral.

It was built by Black artists responding to material conditions — segregation, poverty, violence, and exclusion — with imagination, discipline, and collective care. The question isn’t whether this history exists. It’s whether we’re willing to listen without turning it into background noise.

Listening, real listening, still asks something of us.

And that may be the most radical act left.

“We must recognize that we can’t solve our problem now until there is a radical redistribution of economic and political power.”

— Martin Luther King Jr., 1967