Quand vient la nuit — Fabrice Catérini. What Survives After the Lights Come Back On

Quand vient la nuit — Fabrice Catérini. https://www.saettabooks.com/product/quand-vient-la-nuit

On nightlife, loss, and photographing his way out

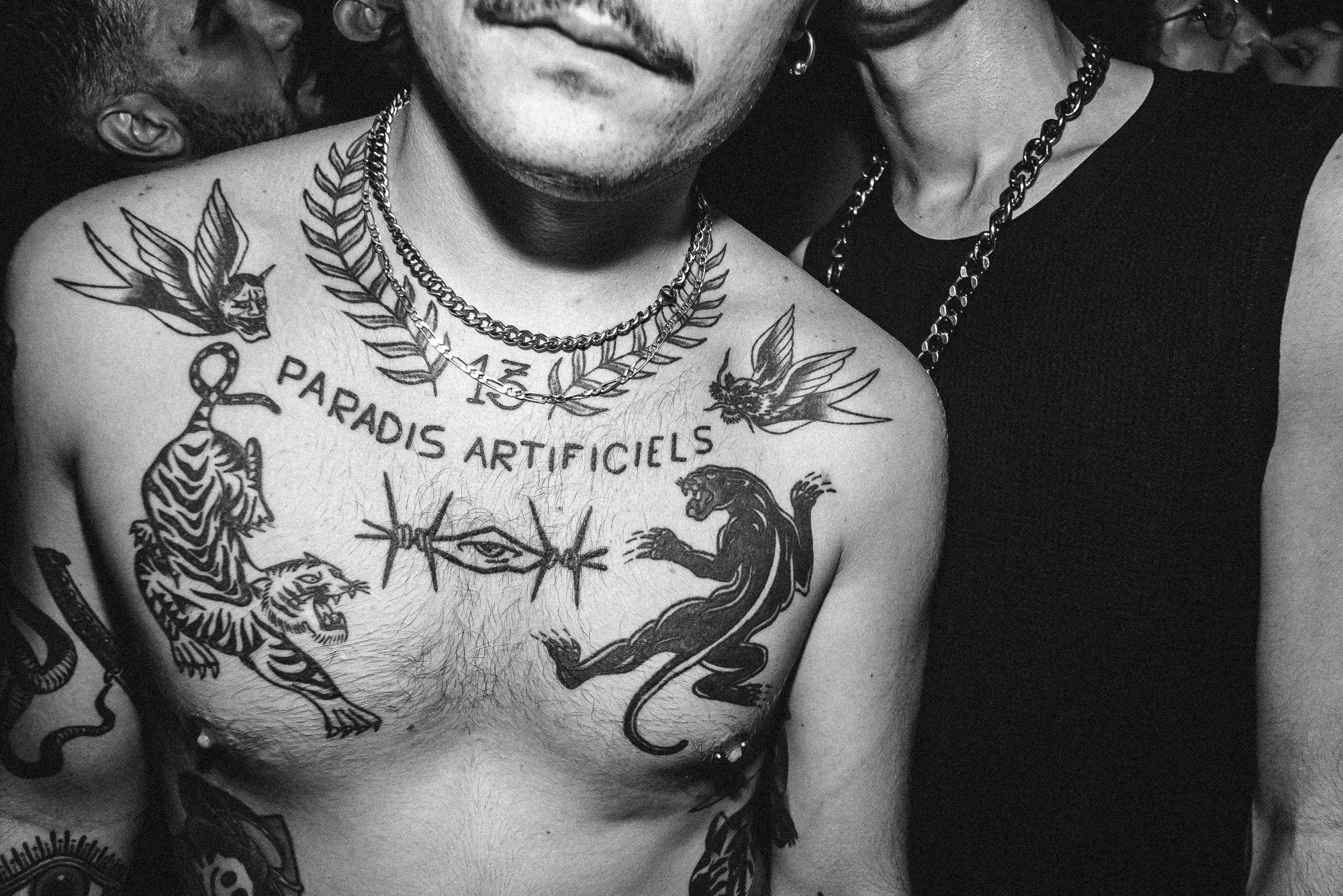

Lyon-born visual artist and filmmaker Fabrice Catérini spent seven years photographing the night as both refuge and danger - chasing love, ecstasy, and collapse across electro-techno dancefloors, streets, and the quiet hours before morning.

His book Quand vient la nuit (“When Night Comes”) reads like a grainy black-and-white poem: club kids, drag queens, sweat and wounds, but also bathtubs, country houses, and snow-muted roads. What ties these fragments together is a single, persistent question: what survives when the lights finally come back on?

Trained in documentary cinema, Catérini co-founded the documentary agency Inediz in 2012, working on long-form projects across Greece, Nigeria, and France before turning toward a more personal and experimental language. His recent work sits at the frontier between day and night, reality and fantasy, the visible and the invisible - often through hybrid forms that blur documentation and fiction.

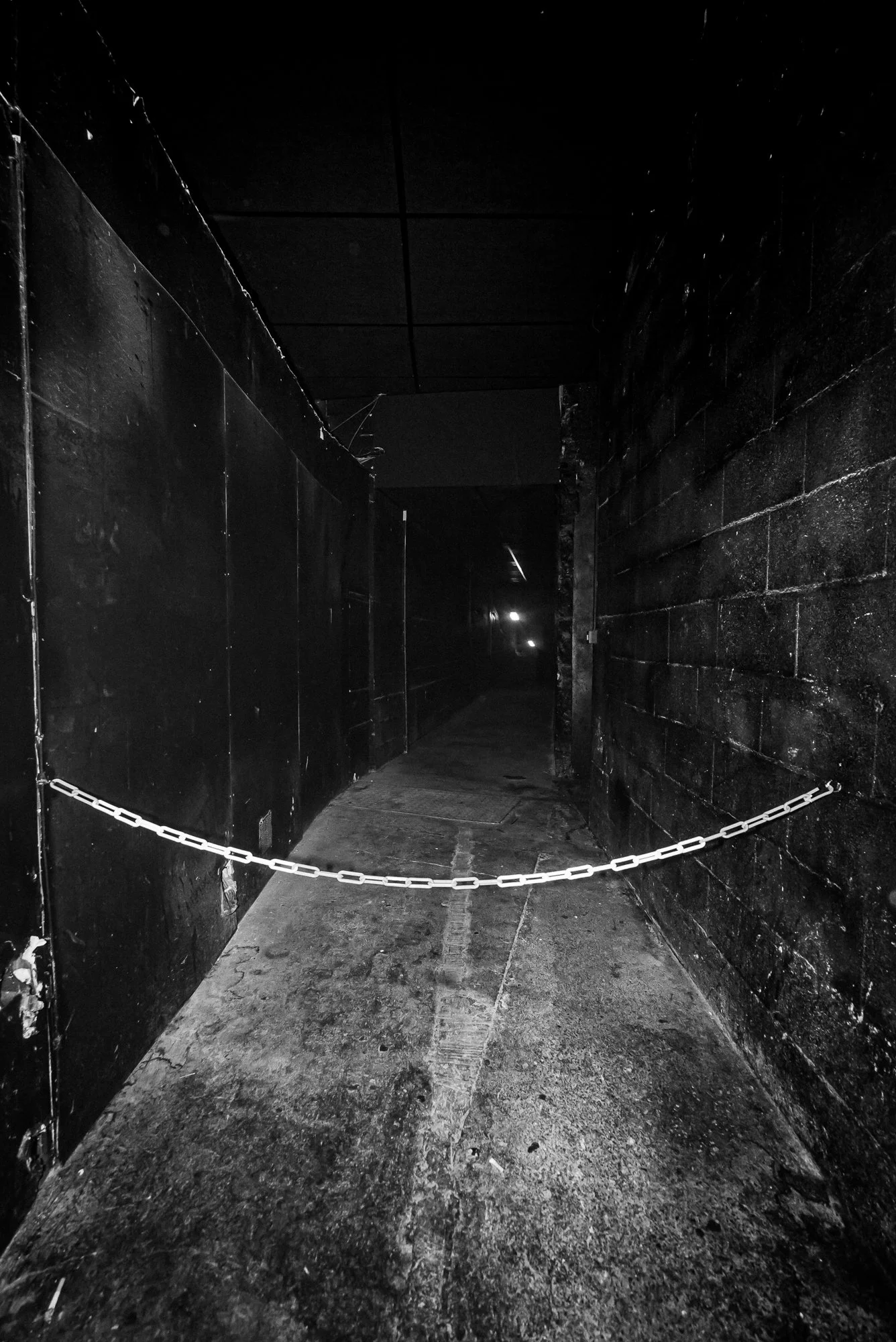

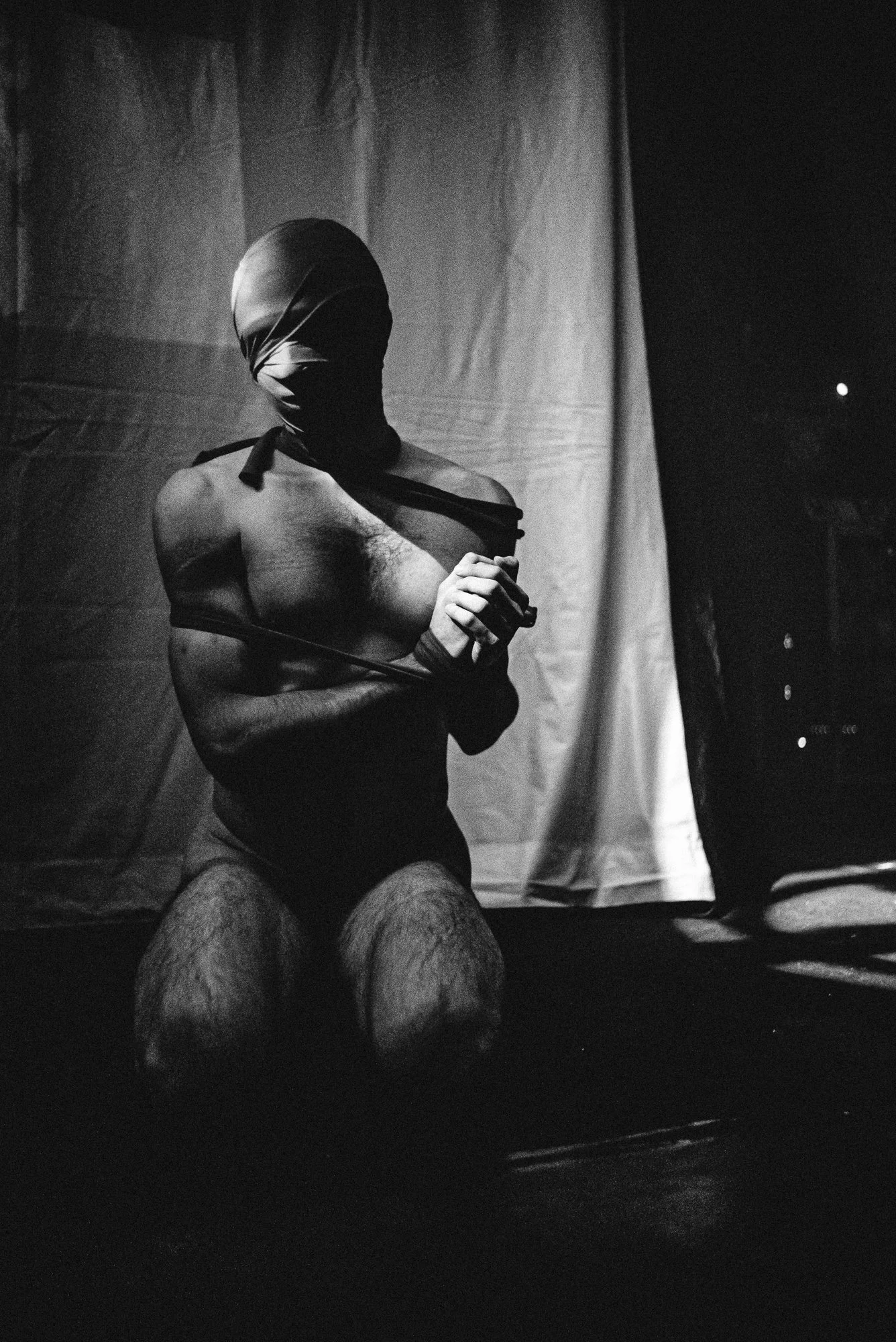

Quand vient la nuit begins where the day ends. Shot over seven years inside clubs, warehouses, and in-between spaces, the project follows a prolonged immersion into nightlife as sanctuary and as swamp - a place where joy, intimacy, self-destruction, and rebirth repeatedly collide.

The book itself becomes part of that experience: a mirror-like cover, dense black pages, and a perforated jacket that reflect the reader back into the night. More than a record of a scene, Quand vient la nuit is a lived-through odyssey - one where photography becomes both obsession and lifeline, pulling its author slowly back toward morning.

The Night as Refuge and Risk

You spent seven years photographing nightlife as both refuge and danger. When you began this project, did you already understand the night as something double-edged, or did that tension only reveal itself over time?

Looking back, and to be completely honest, I think I initially understood the night only as a space of liberation, catharsis, and self-revelation: a place where you can speak and imagine freely, without boundaries or judgment. It harks back to my younger sister — the “wounded woman” in the book — who introduced me to free parties and rave culture in my early twenties. It was never constant: maybe two or three major parties per year, period.

At the time, I was aiming to become a film director and enter the most prestigious film school in France (La Fémis). For the entrance exam, I had to create a visual dossier built around a single word: milieu, which in French can be understood as “social group.” I decided to focus my research on the rave and techno community. I failed the exam by two points out of eighty — shit happens. I then became a photojournalist and documentary filmmaker.

For more than a decade, I barely went to raves, festivals, or clubs. But in 2017, “the rain began to fall.” That same sister developed cancer; I went through betrayal and the collapse of a life trajectory I thought was mine; my father had to sell the family house years after my mother’s death; I witnessed the violence of a neglected disease known as noma while documenting it in Nigeria; and my mentor, Stanley Greene, died that same year. I was in a very dark place.

I slowly retreated into the night as a refuge, first in bars, looking for human connection. Then a friend of a friend said, “Why don’t you come to Badlands? You should come, it’s fun!” Badlands was the name of the first big parties I photographed in Lyon. Step by step, going deeper and deeper, I realized the night was also a place of danger and self-destruction.

I never set out thinking, I want to do a story about nightlife or electronic music. It came naturally. At first, the night felt comfortable, like a velvet blanket — a space of oblivion.

The Wounded Woman

There is a striking photograph of a woman whose skin bears visible wounds and marks. Can you tell the story behind that image — what kind of violence or vulnerability you wanted the viewer to confront?

The woman in the photograph is my younger sister, who had cancer and underwent a double mastectomy. She was the one who asked me to take the picture, I think as a form of therapy: a way to reclaim her wounded body.

I brought a rose because, to me, it is a powerful symbol of life: a combination of beauty and violence, with thorns that can hurt. It was also a reminder of death. It was Stanley Greene’s favorite flower, and his coffin was entirely covered with roses during his burial at Père-Lachaise Cemetery.

Interestingly, when we made the image — or rather, when we captured it — we didn’t notice the visual continuity between her scars, the tattoo, and the branches of the tree in the background. It wasn’t intentional; it simply happened. A reminder that in life, everything is intertwined.

Quand vient la nuit — Fabrice Catérini. https://www.saettabooks.com/product/quand-vient-la-nuit

Looking Back at the Image

When you returned to that photograph later, did it feel more like a document of harm, a love letter to her strength, or a mirror of your own state during those years of shooting?

Looking at this image today, especially knowing that my sister is now doing well, it feels like a symbol of resilience: an invitation to live fully and a reminder of impermanence. Don’t take everything for granted. Try to stay humble. Try to keep things in perspective instead of drowning in a glass of water.

It is both a love letter to my sister and to her strength in overcoming illness, and a reflection of how I understand existence itself.

From Documentary to Confession

Quand vient la nuit — Fabrice Catérini. https://www.saettabooks.com/product/quand-vient-la-nuit

Before Quand vient la nuit, much of your work focused on documentary projects dealing with migration, illness, and political struggle. What shifted when you turned the camera toward your own nocturnal world?

Turning the lens toward my own experience of the night — and toward my inner struggles — helped me better understand others. It also reinforced my understanding of the role and nature of photography. It’s not just about “writing with light,” but about bringing light to others.

You can speak about yourself, but you inevitably end up touching something universal. I sincerely believe this work helped me grow, both as a photographer and as a human being. I learned that sometimes it is necessary to look deep within yourself, without filters but with tenderness. Otherwise, you risk repeating the same mistakes over and over again.

Bukowski has a beautiful line in The Laughing Heart:

“Don’t let it be clubbed into dank submission.”

Becoming Part of the Night

Over time, you became a familiar presence — “the photographer of the night with the mustard-yellow coat and sparkling beret.” How did belonging to that community change what you felt permitted to photograph, and what you chose to leave unseen?

In my photojournalistic work, I mainly focus on long-term projects. For instance, I worked on the Iraqi diaspora for five or six years. When I documented anti-nuclear activists in France, I spent two to three years with them, sleeping in their homes, helping with daily tasks. Of course, I also photographed the “official” side.

What I mean is that in what Stanley Greene, Eugene Smith, and others are calling “concerned photography,” you spend a lot of time with people. It doesn’t necessarily mean being for or against them, nor censoring yourself.

My guiding principle is simple: I can photograph almost anything, as long as I’m not exploiting the pain of others for my own benefit, especially when people are in vulnerable positions. The camera is not a necklace, but a tool. If I’m the only person who can help someone, I put my camera aside. That’s common sense.

And you always have to distinguish between the act of photographing and the act of publishing an image.

Within the nightlife community, I also removed one image from the book — a beautiful photograph of a very singular couple that many people loved. When I contacted the woman again years later, she told me: “It’s a great picture, but I’m going to prosecute the man for sexual violence.” Obviously, the image could not remain in the book.

Burnout and Survival

The book moves between ecstasy and exhaustion, sanctuary and collapse. Was there a moment when you realized the project was no longer just about photographing the night, but about surviving it?

I realized this project was about survival long before I knew it would become a book. It started early, in 2019.

After two days of partying and photographing, I was on assignment for a major New Year’s Eve event: an extravagant night full of drag queens, drag kings, and club kids. I came home exhausted and intoxicated, fell asleep in my office chair while backing up files, and slept for three hours in the wrong position.

When I woke up, I had lost the use of my right hand. Completely. It’s called Saturday night palsy — ironically named. I had to go to physiotherapy twice a week for three months. I couldn’t press the shutter anymore. But I kept trying — relentlessly.

The doctor later told me my recovery, and especially its speed, was remarkable. Photography was vital to me. In a way, what nearly destroyed me also saved me.

From that point on, I knew there was a sword of Damocles hanging over my head. Toward the end of the project, it became even clearer — I felt like a moth circling a streetlamp, just before burning.

Quand vient la nuit — Fabrice Catérini. https://www.saettabooks.com/product/quand-vient-la-nuit

I also became increasingly uncomfortable with what the night scene was turning into, especially with the rise of TikTok techno and the acceleration of ego-driven spectacle. I didn’t want to become one of the mechanisms feeding that machine. It was time to close the cycle.

The Book as Object

The mirror-like cover and dense black pages turn the reader into part of the experience. What role did the physical object play in translating the sensation of the night, beyond the images themselves?

As a team — Mathias Benguigui, Kamil Zihnioglu, Théo Miller (the three co-founders of Saetta Books), and myself — we paid obsessive attention to the book’s editing, physical dimensions, textures, and rhythm.

As a designer, Théo immediately understood what I wanted to convey: a sense of chaos, hallucination, absolute joy alongside profound sorrow — something suspended between solitude and belonging.

You plunge into the night through dark images and dense black pages, then come moments of breathing, lighter images, followed by repetitive photographs from the hospital meals I was served during the cure and my recovery. Then blank pages, a river-like text, and another descent.

The book is built through oscillations, blurring time and space. Combined with the mirror-like cover, it becomes an object readers can appropriate: a surface onto which they can project their own experiences of the night.

Someone recently told me the book reminded them of House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski, which was actually one of the first references I gave Théo when we began imagining the book.

After the Lights Come Back On

After someone closes Quand vient la nuit and their eyes readjust to daylight, what is the one feeling you hope stays with them?

Relief, and hope.

Someone featured in the book once told me: “This book is a gift to you, to me, and to everyone who is ready to accept it.” I couldn’t ask for a better compliment.

I see Quand vient la nuit as a mirror through which readers — but not only the “night owls” — can question and understand their own relationship to the night; but also as a helping hand.

A palindrome runs along both sides of the jacket:

In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni — “We whirl through the night, and we are consumed by fire.”

It’s attributed to Virgil, who guided Dante through Hell toward Paradise.

The first image in the book is my hand, extended into darkness — originally just a light test. It became a recurring motif reflecting my psychological state. The final image shows my hand in broad daylight.

There is always a way out (re-read The Laughing Heart). Photography has been my breadcrumb trail. Each of us must find our own thread — but first, we have to acknowledge our cracks, learn to speak, and be able to ask for help.

Because night, always, eventually gives way to dawn.

Quand vient la nuit — Fabrice Catérini. https://www.saettabooks.com/product/quand-vient-la-nuit

Credits:

interview prepared by Nina Katashvili-Malik

Photography: Fabrice Catérini on instagram

Publishing: Courtesy of Saetta Books

From Quand vient la nuit © Artist